Remembrance and Ritual on Flag Day

June 14, 2021

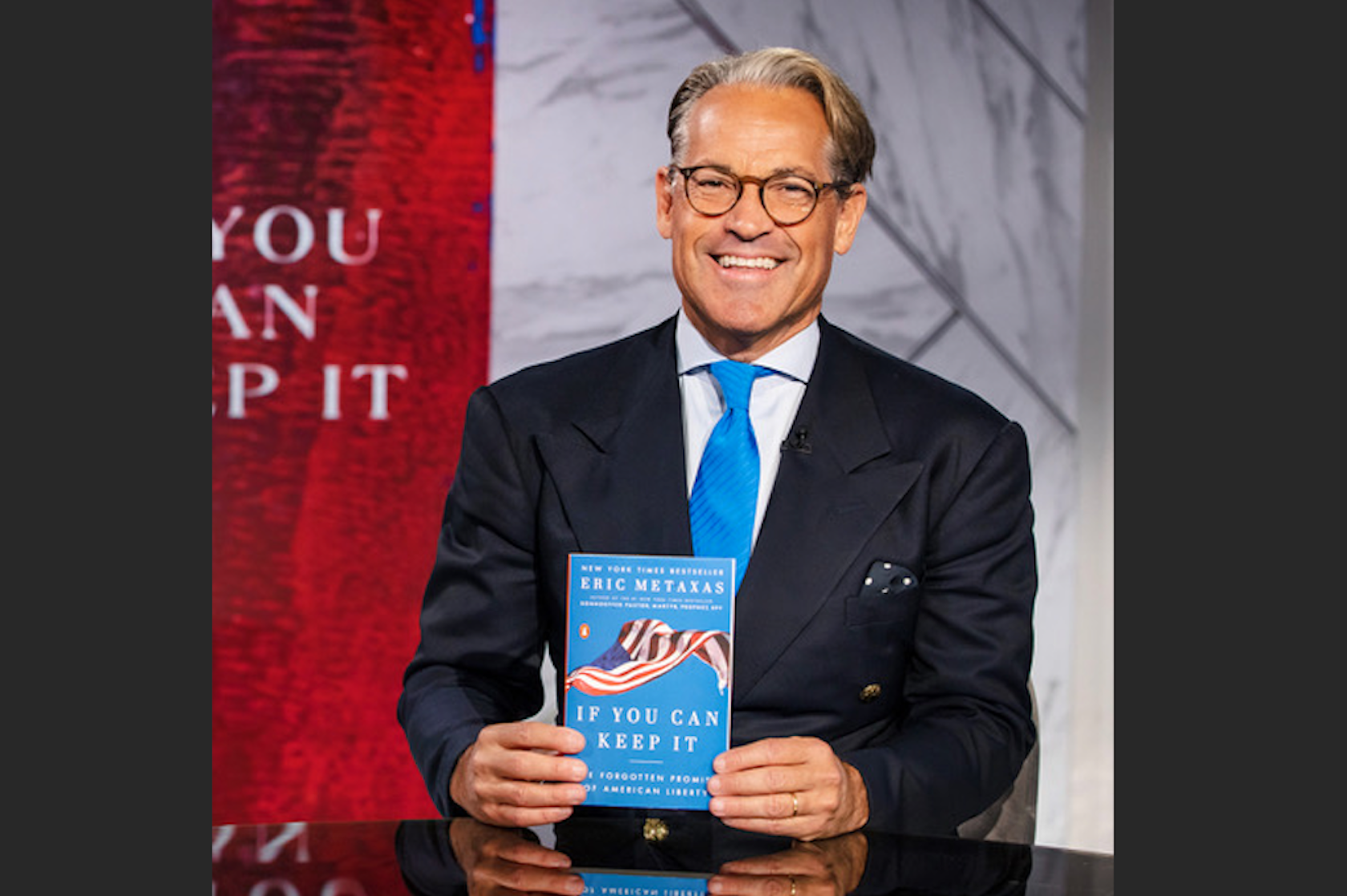

Below is an excerpt from my book IF YOU CAN KEEP IT: The Forgotten Promise of American Liberty.

Remembrance and Ritual

Another way we can love America is through remembrance and ritual. In fact, rituals often exist specifically to help us remember. In the Old Testament, God repeatedly instructs the Israelites to do things on certain dates and to create monuments, precisely so that they will never forget what they have experienced. He knows that if they remember these things it will be that much harder for them to stray, and so every year, among other things, Jews celebrate Passover, with many specific rituals about how and what to eat and what prayers to recite. Every culture must have rituals and in America we have a few, but even in celebrating them we often forget why we are celebrating them. Some people think the Fourth of July is when we celebrate firecrackers and have barbecues, forgetting the reason we explode firecrackers and have barbecues in the first place. Making every Fourth of July, or every Thanksgiving, or every Memorial Day, a day on which we specifically remember something historical about that day would be a way to begin. Perhaps every April 18 we might ask children to recite portions of “Paul Revere’s Ride” and talk about it. On the Fourth of July we might have children recite portions of the Declaration of Independence. On February 12 we might do something to remember Abraham Lincoln and on February 22 we might do something to remember George Washington. We should do these things in our communities, in front of our town halls, and in front of our libraries, and in our churches and synagogues and mosques, and of course we must do them in our schools. Doing such things in our schools is perhaps the principal way we can help teach the next generation what it means to love our country. In fact, I still remember something that I did on June 14, 1973.

I was just shy of my tenth birthday and our fifth- grade teacher, Mrs. Saul, told us that we were all going outside to celebrate Flag Day. I’d never heard of Flag Day before. Later I learned that the Revolutionary Congress adopted the Stars and Stripes as the official flag of the new country on June 14, 1777, and the date has been designated Flag Day ever since. So we marched out of the classroom to the flagpole in front of the school. We were a small class of fifteen and we stood around the flagpole in a circle as Mr. Piccarello, who was my trumpet teacher, joined us. I was surprised to see that he did not have a brass trumpet, as I did, but a beautiful silver cornet. He put it to his lips, and as we stood around the flagpole he played “My Country, ’Tis of Thee,” and we sang:

My Country, ’tis of thee,

Sweet land of liberty,

Of thee I sing!

Land where our fathers died,

Land of the Pilgrims’ pride

From every mountainside,

Let freedom ring!

After that he played taps, which is often played at flag ceremonies, and we listened. It was sonorous and solemn and beautiful. Those moments around the flagpole on that June day over forty years ago so pricked my heart that I still think of them with the deepest reverence. It seems to me like a holy memory, like something from another time, from an innocent time beyond this world, from the golden world that is childhood. But what were we doing there that day? I realize now that we were participating in a ritual and I realize that, like all rituals, it was designed to evoke something in us. But what? I think now I know. We were being taught to love our country.

There was something about what we are doing that told us all that somehow this was important. It was telling us that that flag there is more than a flag. It is more than a red- white- and- blue banner that droops or waves. It is a sacred symbol that points toward something beyond itself, that points to the real thing that it represents, to America, the country that we’ve been learning about in this school year, the country that was “born in liberty” and for which all of those heroes fought and died and which you are now entrusted to keep. Nothing of the kind was said in words, but it didn’t need to be said. On levels that are beyond words it was communicated, and without words we took it in.

There weren’t many more moments like this in my education. Already by 1973 these sorts of patriotic rituals were on their way out, especially in public schools and especially in the North. But Mrs. Saul had started teaching in the 1930s, so she had likely been doing this for four decades, and now, in her last year of teaching, we fifteen students got to experience the very tail end of what one might call a Norman Rockwell, Frank Capra view of America, of a nation made up mainly of small towns, where people were proud to gather around flagpoles and to celebrate our common history and heritage.

Those rituals were making us part of something, linking us to all those around the country that Flag Day and other Flag Days and other patriotic days throughout the nation’s history. When we were older we would think of this day and it would mean something to us. It was one of those “mystic chords of memory” of which Lincoln spoke, that bound us to others in a way that was beautiful and true. The magic of it is that you cannot boil it down to something. You cannot reduce it. It was not indoctrination. It was beautiful, pointing to something beyond itself, pointing to something noble and true and eternal. We were being taught to love America.

Our affections were being shaped and directed. We were being pointed to something noble and ennobling: our sense of ourselves as a great nation worth celebrating, a nation whose ideas are worth spreading around the globe. Which brings me back to another idea, that our love for what is good in ourselves personally and what is good in our country actually causes us to love what is good in others and in other countries. That is the paradox of true love. To love the goodness in any one thing is to love goodness itself. To love one thing to the exclusion of the goodness in other things is not to love that one thing at all but to make a false idol of it and to hate real goodness.