Introduction to AMAZING GRACE

August 20, 2009

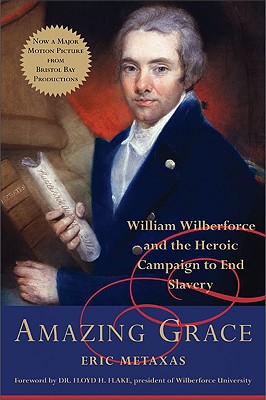

This is the Introduction to my book Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the Heroic Campaign to End Slavery.

* *

WE OFTEN HEAR ABOUT PEOPLE WHO “need no introduction,” but if ever someone did need one, at least in our day and age, it’s William Wilberforce. The strange irony is that we are talking about a man who changed the world, so if ever someone should not need an introduction — whose name and accomplishments should be on the lips of all humanity — it’s Wilberforce.

What happened is surprisingly simple: William Wilberforce was the happy victim of his own success. He was like someone who against all odds finds the cure for a horrible disease that’s ravaging the world, and the cure is so overwhelmingly successful that it vanquishes the disease completely. No one suffers from it again — and within a generation or two no one remembers it ever existed.

The roots of the thing Wilberforce was trying to uproot had been growing since humans first walked on the planet, and if they had been real roots, they would have reached to the molten core of the earth itself. They ran so deep and so wide that most people thought that they held the planet together.

The opposition that he and his small band faced was incomparable to anything we can think of in modern affairs. It was certainly unprecedented that anyone should endeavor, as if by their own strength and a bit of leverage, to tip over something about as large and substantial and deeply rooted as a mountain range. From where we stand today — and because of Wilberforce — the end of slavery seems inevitable, and it’s impossible for us not to take it largely for granted. But that’s the wild miracle of his achievement, that what to the people of his day seemed impossible and unthinkable seems to us, in our day, inevitable.

There’s hardly a soul alive today who isn’t horrified and offended by the very idea of human slavery. We seethe with moral indignation at it, and we can’t fathom how anyone or any culture ever countenanced it. But in the world into which Wilberforce was born, the opposite was true. Slavery was as accepted as birth and marriage and death, was so woven into the tapestry of human history that you could barely see its threads, much less pull them out. Everywhere on the globe, for five thousand years, the idea of human civilization without slavery was unimaginable.

The idea of ending slavery was so completely out of the question at that time that Wilberforce and the abolitionists couldn’t even mention in publicly. They focused on the lesser idea of abolishing the slave trade — on the buying and selling of human beings — but never dared speak of emancipation, of ending slavery itself. Their secret and cherished hope was that once the slave trade had been abolished, it would then become possible to being to move toward emancipation. But first they must fight for the abolition of the slave trade; and that battle — brutal and heartbreaking — would take twenty years.

Of course, finally winning that battle in 1807 is the single towering accomplishment for which we should remember Wilberforce today, whose bicentennial we celebrate, and whose celebration occasions a movie, documentaries, and the book you now hold. If anything can stand as a single marker of Wilberforce’s accomplishments, it is that 1807 victory. It paved the way for all that followed, inspiring the other nations of the world to follow suit and opening the door to emancipation, which, amazingly, was achieved three days before Wilberforce died in 1833. He received the glorious news of his life-long goal on his deathbed.

Wilberforce was one of the brightest, wittiest, best connected, and generally talented men of his day, someone who might well have become prime minister of Great Britain if he had, in the words of one historian, “preferred party to mankind.” But his accomplishments far transcend any mere political victory. Wilberforce can be pictured as standing as a kind of hinge in the middle of history: he pulled the world around a corner, and we can’t even look back to see where we’ve come from.

Wilberforce saw much of what the rest of the world could not, including the grotesque injustice of one man treating another as property. He seems to rise up out of nowhere and with the voice of unborn billions — with your voice and mine – shriek to his contemporaries that they are sleepwalking through hell, that they must wake up and must see what he saw and know what he knew — and what you and I know today — that the widespread and institutionalized and unthinkably cruel mistreatment of millions of human beings is evil and must be stopped as soon as conceivably possible — no matter the cost.

How is it possible that humanity for so long tolerated what to us is so obviously intolerable? And why did just one small group of people led by Wilberforce suddenly see this injustice for what it was? Why in a morally blind world did Wilberforce and a few others suddenly sprout eyes to see it? Abolitionists in the late eighteenth century were something like the characters in horror films who have seen “the monster” and are trying to tell everyone else about it — and no one believes them.

To fathom the magnitude of what Wilberforce did we have to see that the “disease” he vanquished forever was actually neither the slave trade nor slavery. Slavery still exists around the world today, in such measure as we can hardly fathom. What Wilberforce vanquished was something even worse than slavery, something that was much more fundamental and can hardly be seen from where we stand today: he vanquished the very mind-set that made slavery acceptable and allowed it to survive and thrive for millennia. He destroyed an entire way of seeing the world, one that had held sway from the beginning of history, and he replaced it with another way of seeing the world. Included in the old way of seeing things was the idea that the evil of slavery was good. Wilberforce murdered that old way of seeing things, and so the idea that slavery was good died along with it. Even though slavery continues to exist here and there, the idea that it is good is dead. The idea that it is inextricably intertwined with human civilization, and part of the way things are supposed to be, and economically necessary and morally defensible, is gone. Because the entire mind-set that supported it is gone.

Wilberforce overturned not just European civilization’s view of slavery but its view of almost everything in the human sphere; and that is why it’s nearly impossible to do justice to the enormity of his accomplishment; it was nothing less than a fundamental and important shift in human consciousness.

In typically humble fashion, Wilberforce would have been the first to insist that he had little to do with any of it. The facts are that in 1785, at age twenty-six and at the height of his political career, something profound and dramatic happened to him. He might say that, almost against his will, God opened his eyes and showed him another world. Somehow Wilberforce saw God’s reality — what Jesus called the Kingdom of Heaven. He saw things he had never seen before, things that we quite take for granted today but that were as foreign to his world as slavery is to ours. He saw things that existed in God’s reality but that, in human reality, were nowhere in evidence. He saw the idea that all men and women are created equal by God, in his image, and are therefore sacred. He saw the idea that all men are brothers and that we are all our brothers’ keepers. He saw the idea that one must love one’s neighbor as oneself and that we must do unto others as we would have them do unto us.

These ideas were at the heart of the Christian Gospel, and they had been around for at least eighteen centuries by the time Wilberforce encountered them. Monks and missionaries knew of these ideas and lived them out in their limited spheres. But no entire society had ever taken these ideas to heart as a society in the way that Britain would. That was what Wilberforce changed forever.

As a political figure, he was uniquely positioned to link these ideas to society itself, to the public sphere, and the public sphere, for the first time in history, was able to receive them. And so Wilberforce may perhaps be said to have performed the wedding ceremony between faith and culture. We had suddenly entered a world in which we would never again ask whether it was our responsibility as a society to help the poor and the suffering. We would only quibble about how, about the details — about whether to use public funds or private, for example. But we would never again question whether it was our responsibility as a society to help those less fortunate. That had been settled. Today we call this having a “social conscience,” and we can’t imagine any modern, civilized society without one.

Once this idea was loosed upon the world, the world changed. Slavery and the slave trade would soon be largely abolished, but many lesser social evils would be abolished too. For the first time in history, groups sprang up for every possible social cause. Wilberforce’s first “great object” was the abolition of the slave trade, but his second “great object,” one might say, was the abolition of every lesser social ill. The issues of child labor and factory conditions, the problems of orphans and widows, of prisoners and the sick — all suddenly had champions in people who wanted to help those less fortunate than themselves. At the center of most of these social ventures was the Clapham Circle, an informal but influential community of like-minded souls outside London who plotted good deeds together, and Wilberforce himself was at the center of Clapham. At one point he was officially linked with sixty-nine separate groups dedicated to social reform of one kind or another.

Taken all together, it’s difficult to escape the verdict that William Wilberforce was simply the greatest social reformer in the history of the world. The world he was born into in 1759 and the world he departed in 1833 were as different as lead and gold. Wilberforce presided over a social earthquake that rearranged the continents and whose magnitude we are only now beginning to fully appreciate.

Unforeseen to him, the fire he ignited in England would leap across the Atlantic and quickly sweep across America — and transform that nation profoundly and forever. Can we imagine an America without its limitless number of organizations dedicated to curing every social ill? Would such an America be America? We might not wish to credit Wilberforce with inventing America, but it can reasonably be said that the America we know wouldn’t exist without Wilberforce.

As a result of the efforts of Wilberforce and Clapham, social “improvement” was so fashionable by the Victorian era that do-gooders and do-goodism had become targets of derision, and they have been so ever since. We have simply forgotten that in the eighteenth century, before Wilberforce and Clapham, the poor and suffering were almost entirely without champions in the public or private sphere. We who are sometimes obsessed with social conscience can no longer imagine a world without it, or a society that regards the suffering of the poor and others as the “will of God.” Even where this view does exist, as in societies and cultures informed by an Eastern, karmic view of the world, we refuse to believe it. We arrogantly seem to insist that everyone on the planet think as we do about society’s obligation to the unfortunate, but they don’t.

No politician has ever used his faith to a greater result for all of humanity, and that is why, in his day, Wilberforce was a moral hero far more than a political one. Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Nelson Mandela in our own time come closest to representing what Wilberforce must have seemed like to the men and women of the nineteenth century, for whom the memory of what he had done was still bright and vivid.

Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln both hailed him as an inspiration and example. Lincoln said every schoolboy knew Wilberforce’s name and what he had done. Frederick Douglass gushed that Wilberforce’s “faith, persistence, and enduring enthusiasm” had “thawed the British heart into sympathy for the slave, and moved the strong arm of that government to in mercy put an end to his bondage.” Poets and writers such as Harriet Beecher Stowe and George Eliot sang his praises, as did Henry David Thoreau and John Greenleaf Whittier. Byron called him “the moral Washington of Africa.”

The American artist and inventor Samuel Morse said that Wilberforce’s “whole soul is bent on doing good to his fellow men. Not a moment of his time is lost. He is always planning some benevolent scheme, or other, and not only planning but executing … Oh, that such men as Mr. Wilberforce were more common in this world. So much human blood would not be shed to gratify the malice and revenge of a few wicked, interested men.”

The American abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison went further yet. “His voice had a silvery cadence,” he said of Wilberforce, “his face a benevolently pleasing smile, and his eye a fine intellectual expression. In his conversation he was fluent, yet modest; remarkably exact and elegant in his diction; cautious in forming conclusions; searching in his interrogations; and skillful in weighing testimony. In his manner he combined dignity with simplicity, and childlike affability with becoming gracefulness. How perfectly do those great elements of character harmonize in the same person, to wit — dovelike gentleness and amazing energy — deep humility and adventurous daring! … These were mingled in the soul of Wilberforce.”

An Italian nobleman who saw Wilberforce in his later years wrote: “When Mr. Wilberforce passes through the crowd on the day of the opening of Parliament, every one contemplates this little old man, worn with age, and his head sunk upon his shoulders, as a sacred relic: as the Washington of humanity.”

We blanch at such encomia today, for indeed, ours is an age deeply suspicious of greatness. Watergate seems to have come down upon us like a portcullis, cutting us off forever from anything approaching such hero worship, especially of political figures. With the certainty of a Captain Queeg, we are forever on the lookout for the worm in the apple, the steroid in the sprinter or slugger. And lurking behind every happy biographical detail we see the skulking figure of Parson Weems and his pious fibs about cherry trees and — of all things — telling the truth.

If ever someone could restore our ability to again see simple goodness, it should be Wilberforce. If we cannot cheer someone who literally brought “freedom to the captives” and bequeathed to the world that infinitely transformative engine we call a social conscience, for whom may we ever cheer? Especially knowing that he has been more forgotten than remembered, and that he himself would have been the first to denigrate his accomplishments — as we can see from his diaries and letters, which show us that he went to the grave sincerely and deeply regretted that he hadn’t done much more.

In the thick of the battle for abolition, one of its many dedicated opponents, Lord Melbourne, was outraged that Wilberforce dared inflict his Christian values about slavery and human equality on British society. “Things have come to a pretty pass,” he famously thundered, “when one should permit one’s religion to invade public life.” For this lapidary inanity, the jeers and catcalls and raspberries and howling laughter of history’s judgment will echo forever — as they should.

But after all, it is a very pretty pass indeed. And how very glad we are that one man led us to that pretty pass, to that golden doorway, and then guided us through the mountains to a world we hadn’t known could exist.

END