A Few (Passionate) Thoughts on America!

June 9, 2016

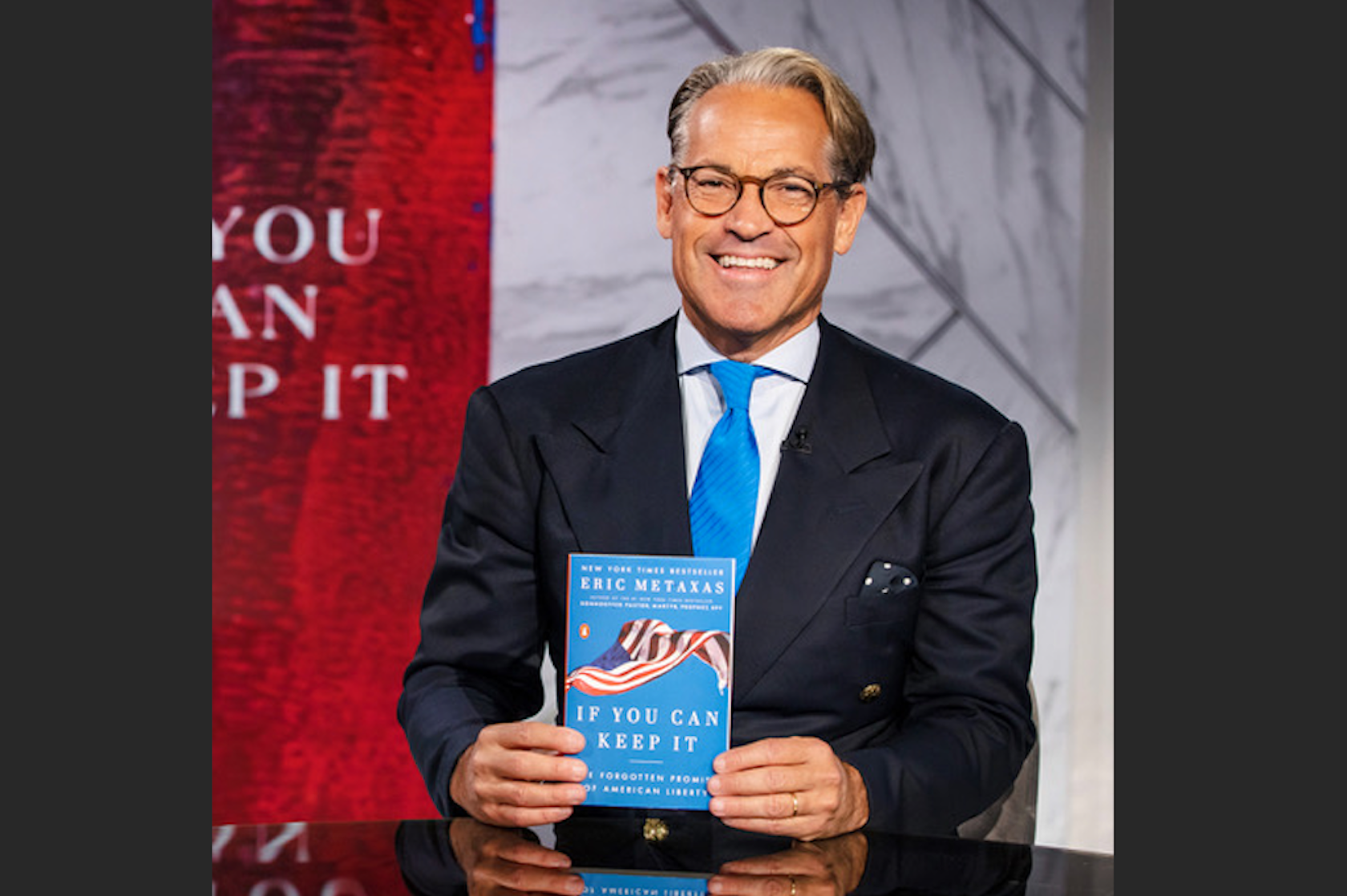

How did the idea for the book first come about?

How did the idea for the book first come about?

Honestly, I’ll never forget it. I was listening to the author Os Guinness give a speech about the Founders unique idea of “ordered liberty” and he described it in terms of what he called the “Golden Triangle of Freedom.” It all made perfect sense, but I was shocked and embarrassed to realize that somehow I’d managed never to have heard any of this before and that neither had most people I knew. So after I stopped perspiring, I tried to figure out how a reasonably well-educated American could miss these ideas that are utterly foundational and central to what America is and who we Americans are as a people? What could have happened? Then I read his book A Free People’s Suicide and was staggered further still, because I realized that if this country — which was expressly founded on these ideas — had ceased to understand them and pass them on to the next generation, it would eventually cease to be America in any real sense, and I realized that that’s precisely what had been happening in the last four or so decades. To say that I had a sense of urgency about it is an understatement. I talked about it whenever I went and pushed Os’s book on everyone I knew, and as my thinking on it all expanded I realized I needed to get my own thoughts into a book — and to promote that book as widely and forcefully as any book I would ever write. Because I saw that once America devolved to being “America”, the whole world would suffer. Despite our ills and shortcomings, we have been a beacon of liberty to the whole world — my parents, for example, as I discuss in the book, who came from places of misery to this place that represented hope and a future — and if that beacon should go out in our generation, what Lincoln called the “last best hope of earth” would have vanished. It would be as though we had effectively committed suicide because we had forgotten to eat. So to cut to the chase, this book is about saving America, and in doing that, saving the world. That’s all. No pressure, right?

Throughout the book you refer to the popular quote “America is great because America is good, and if America ever ceases to be good, America will cease to be great.” What does that mean to you and how has America strayed from that?

This has manifested itself differently between liberals and conservatives. For example, conservatives have sometimes felt that America’s greatness was indeed that kind of chest-beating pride that people have misunderstood as “American exceptionalism,” and have forgotten that we have an important role to play in reaching out to the rest of the world, in welcoming others to our shores and in sharing our blessings — whether ideas regarding freedom or material blessings — with others. They’ve sometimes acted as though greed were indeed good, as though laissez-faire capitalism didn’t require a moral component to work as it should. And they’ve sometimes acted as though self-government didn’t require virtue — and a people and ethos that that prized virtue and hailed it as a social good. On the other hand, liberals have mostly in recent decades misunderstood the role that faith has played in our history and will continue to play if we allow it to do so. People of faith have been at the forefront of the Abolitionist movement and the Civil Rights movement. These were not secular movements. Our history in doing good could not and did not happen without people of serious faith playing a vital role, so to allow a new secularism to push people of faith out of the cultural conversation is to deny our history and to prevent our future together in any meaningful sense.

In If You Can Keep It, you write that self-government cannot exist without virtuous leaders. What do you think has been the biggest cause of the erosion of virtue in our modern-day political leaders?

I don’t think our leaders are less virtuous than the rest of us. I simply think that the idea of virtue — and honor and duty and dignity — have fallen out of favor as concepts generally, and it’s affected our leaders. The ideas of virtue and honor and dignity and duty — all of which were constantly on the lips and in the minds of the men who founded our country — are today considered antiquated or corny or as part of a way of thinking that allowed an old-fashioned patriarchal, slave-owning culture to hold power. At best these concepts are considered quaint. But we make a grave mistake by abandoning them. They are what made everything else possible, all the things we prize. But as C.S. Lewis said, “We laugh at honor and are shocked to find traitors in our midst.” In the “ordered liberty” given us to us by the founders, there are no substitutes for these things. We either prize them and govern ourselves and are free, or we forget about them and are eventually governed from above as we were when King George III sat on the throne in London. “We the people” cannot exist without some sense of leading and governing ourselves, and those things are at the heart of that thinking.

Today, the phrase “American exceptionalism” has mostly negative connotations. How did the idea of “American exceptionalism” help our early democracy get off the ground? Why is it still an important phrase today?

As I explain in the book, the idea of “American exceptionalism” is today completely misunderstood. The real idea behind it is very different from the chest-beating “look at me, I’m the best” attitude that most people associate with trash-talking nationalism. The fundamental idea of “exceptionalism” comes from the first pages of the Bible, and it means that God blesses a people in order for them to bless others. If this country has been blessed, and it has, that was always meant to be thought of as a way for us to use those blessings to bless the whole world. To bless immigrants and to bless those beyond our borders and to bless those within our borders who were struggling. The “how” is the big question, but there is no question of the “whether.” It is why we are exceptional and we cease to be exceptional — and will cease to be blessed — when we forget that, and yes, we are forgetting that.

How does faith play a role in “keeping” America?

The Founders knew and really took for granted the role of faith as the secret ingredient in the “ordered liberty” that was America. They knew that only a virtuous people could govern themselves, and a robust expression of faith was utterly crucial the idea of self-government they launched into the world. The most secular of our founders — Franklin and Jefferson, for example — understood this and valued it deeply. There was staggering unanimity on this subject and the idea in recent years that we could pull off what we have without a population of people who understood this and lived it out or at least valued it in the lives of others is not less than suicidal.

What do our potential Presidential candidates need to learn about the founding fathers in order to “keep the republic?”

How about “everything”? They could start there. Even those few candidates who have understood and discussed some of these ideas haven’t understood all of them and given where we are in history, that’s a deeply disturbing development. Candidates could get away with being vague on these things in the past, but we’ve gotten to the point where we have no more fuel in the tank. Our reserves are spent and we need a crash course or primer on these things, which this book means to be. It’s kind of like a cut flower. It can continue to look great for a while, but at some point the fact that it’s cut off from its roots will begin to show. We are at that point in America. Either we reconnect to our roots or its game over.

What do you think our founding fathers would think of America today?

I think on the one hand they would be astonished that we have lasted this long and on the other hand they would be shocked that we don’t realize how astonishing it is. From their point of view, the birth of America and her launching into the ocean of history was an implausibility and a miracle. They all acknowledged that. It simply doesn’t make sense that we should have come into existence — or once we came into existence, we ought to have vanished after a few decades. So I think they would be astonished that we are still here, 240 years after they met in Independence Hall. But I think they would be even more astonished that we don’t realize what a miracle our existence is, that we basically now take it for granted, and have therefore ceased to do all we can to make sure we continue to exist. I think they would shout about it from the rooftops till they were hoarse, that we must recover a sense of how extraordinary our existence in history is and must then do everything conceivably possible to make sure we continue to exist. They would risk their lives to communicate this, just as they did then.

How do we as Americans strike a balance between acknowledging the faults and mistakes of the past and present, and honoring the things and ideas that make America great?

It’s part of our greatness that we’ve been able to acknowledge our faults. But at this point we have done that to a fault. We are stuck in a fault-finding mode and it is killing us. We now need to remember that only a nation that is great could ever have the strength to publicly acknowledge its faults and deal with them — in the way that we abolished slavery, for example, and in the way that we dealt with the Civil Rights issue. And now we must step back and acknowledge all the things that we have done that are good and heroic and noble, and must celebrate the heroes who have sacrificed life and limb and their “sacred honor” to get us here. If we do not begin to do that seriously and urgently, we will negate all the good we’ve done in acknowledging our faults and will cease to be great in any sense, and will cease to be America in any sense. It’s that serious. The pendulum needs to come back toward the heroic side of things.

What makes you most proud to be an American?

My parents. I tell their stories in the book, but the idea that these two young Europeans could in the 1950s escape the hunger and other horrors of war-torn Europe and be welcomed in a country that would give them hope and opportunities to raise a family and eve buy a home and raise two children with hopes beyond anything they had ever dreamt for themselves is proof positive that this nation is something we must acknowledge as glorious and important in this world, that we must celebrate and that we must love.

What do you hope the takeaway will be for Americans who read If You Can Keep It?

I hope they will understand this message of who we are as a nation — and that once they do that they will understand that it is their duty to spread the message and to live it out. It is their solemn duty to those who have gone before them, who have sacrificed bitterly to give them what they now have and have mostly taken for granted, to our great shame. It is a duty, but it is also an unspeakable privilege to be able to do that, to be part of history, to be able to bless future generations and people around the globe. If we fail to see that and to appreciate that, we are to be deeply pitied. My hope in writing this book is that that won’t happen, that people get this and will press this message into the hands of everyone they know and say, this is our time. My hope is that they will see that we have understood these things just in time — just before we ride blithely off the cliff looming ahead — and now we’ve got to live them and teach them to the next generation. It’s a sobering thing to think that we almost missed this and slipped into oblivion, that we’ve been given a second chance, and now that we see that, we can never let it die. Or we must die trying. I’m not sure why we’ve been given this second chance, but not to take it would be worse than never getting it at all.